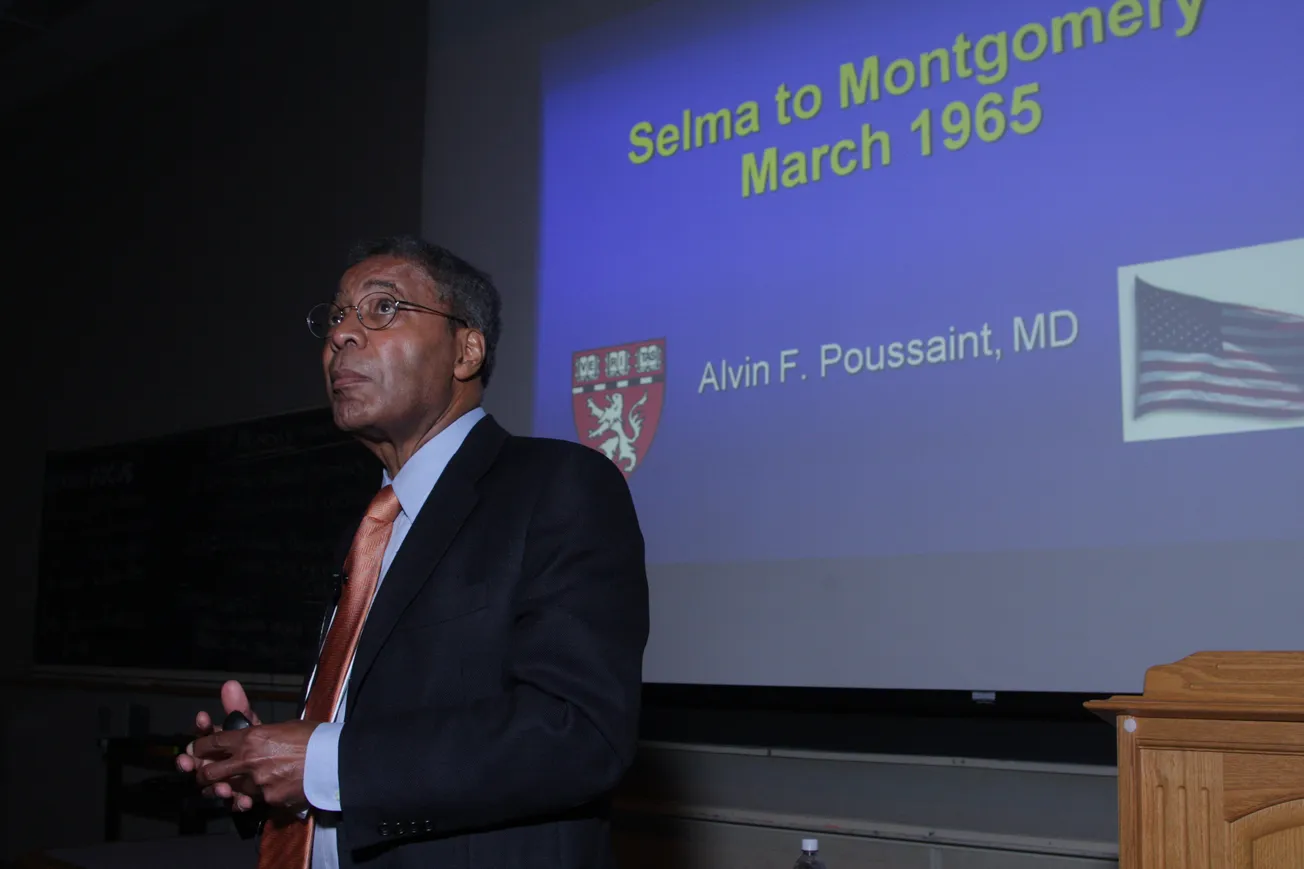

Dr. Alvin Poussaint, a noted Ivy League psychiatric scholar who wrote on the African-American response to racism, has died in Massachusetts following a short illness. He was 90 years old and his wife, Dr. Tina Young Poussaint of Harvard Medical School (HMS), announced his passing on Feb. 24.

“Dr. Poussaint was a legendary figure at HMS and beyond. He was an influential psychiatrist, scholar, and advocate for equitable access and opportunity,” said Dr. George Q. Daley, Harvard’s medical school dean.

“He was a prodigious and careful thinker who married meticulous, evidence-based social science with insightful, pragmatic commentary.”

HMS mourns the loss of psychiatrist and civil rights activist Alvin Poussaint, who died on Feb. 24 at age 90 https://t.co/khjgcpWb9R

— Harvard Medical School (@harvardmed) February 28, 2025

Born to Haitian immigrants in Harlem in 1934, Poussaint was raised in a large Catholic family with seven siblings. He attended the elite Stuyvesant High School in Lower Manhattan, where he was one of only a few Black students. His mother, who died when he was a junior, wanted him to consider the priesthood but he instead drifted from the Church and decided to become a doctor.

Poussaint matriculated at Columbia University, where he studied pharmacology, and later enrolled at Cornell Medical School as the only Black member of his class, graduating in 1960. His experiences of anti-Black racism from a young age inspired his area of focus: African-American mental health.

An active member of the Civil Rights Movement, Poussaint served as chief resident of the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute only briefly before moving to the South to serve directly in the Black freedom struggle.

Recruited by Bob Moses after the 1964 triple murder of an interracial group of activists in rural Mississippi, Poussaint served in the state capital as the Southern field director for the Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR), a group within the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee dedicated to healthcare for activists working in the movement.

During his time with MCHR, Poussaint was a pivotal figure in the fight to desegregate hospitals nationwide, a goal reached by 1965 with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Medicare Act of 1965. He also became close friends with Jesse Jackson.

Poussaint remained for two years in Mississippi before a short stint at Tufts University in Massachusetts—just two miles from Harvard, where he was hired in 1969 as the associate dean of student affairs at the medical school, and also served as a professor of psychiatry.

During his half-century tenure in Cambridge, Poussaint became known for his theories on the nature of racism in America, including his categorization of it as a mental illness in a 1999 op-ed for the New York Times. He also worked to combat negative stereotypes resulting from rampant intra-cultural crises in the late 20th-century Black community, including drug abuse, crime, poverty, and fatherlessness.

Poussaint framed the various ills as resulting at least in part from the various traumas of racism, which he argued led African Americans—and especially men—to engage in self-destructive behaviors. Instead of framing this as primarily a Black social defect, however, he wrote in his famous 1972 text “Why Blacks kill Blacks” that it was actually racist White Americans who showed signs of psychological instability.

Poussaint’s work to combat racism included his promotion of positive role models for young African Americans, including helping to steer silver screen scripts as a consultant for shows like “The Cosby Show” and “A Different World.” He played similar roles for government agencies in Washington, including the FBI, and founded the Baker Center for Children and Families in 1978.

At Harvard, Poussaint pushed for increased diversity in both the medical field and in medical education, having been hired to lead the school’s Office of Recruitment and Multicultural Affairs after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Soon after, Poussaint helped found the Black Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association.

Poussaint’s notable works also included advocacy for healthy Black parenting strategies, a topic covered in his books “Black Child Care” (1975) and “Raising Black Children” (1992). In 2000, he published on the novel concept of post-traumatic slave syndrome with “Lay My Burden Down,” co-authored in 2000 with Amy L. Alexander, and co-wrote “Come on, People: On the Path from Victims to Victors” with Bill Cosby in 2007.

Poussaint retired from Harvard in 2019, having received various honors for his work both inside and beyond the academy. These include the school’s Diversity Lifetime Achievement Award, a regional Emmy Award, the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Herbert W. Nickens Award, the John Hope Franklin Award from Diverse: Issues In Higher Education, and the American Psychiatric Association’s Distinguished Service Award, the American Black Achievement Award in Business and the Professions, and the John Jay Award for distinguished professional achievement.

As a testament to his legacy, HMS inaugurated the Alvin F. Poussaint, MD, Visiting Lecture in 2005, and his own undergraduate enrichment subcommittee at the school has since become the Poussaint Pre-matriculation Summer Program.

“Dr. Poussaint’s life and work had an immeasurable impact on the profession and practice of medicine in this country,” said Bernard Chang, the dean for medical education at HMS.

“Those of us who had a chance to know him personally will always remember the kind, just, and thoughtful approach he took to everything he did.”

Poussaint is survived by his wife of 32 years, Tina; his children Alan and Alison; and a sister, Dolores Nethersole. He is also survived by his first wife, Anne Ashmore-Hudson of Washington.

A celebration of Poussaint’s life is to be announced at a later date. Davis Funeral Home in Roxbury, Massachusetts, is handling arrangements.

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger.