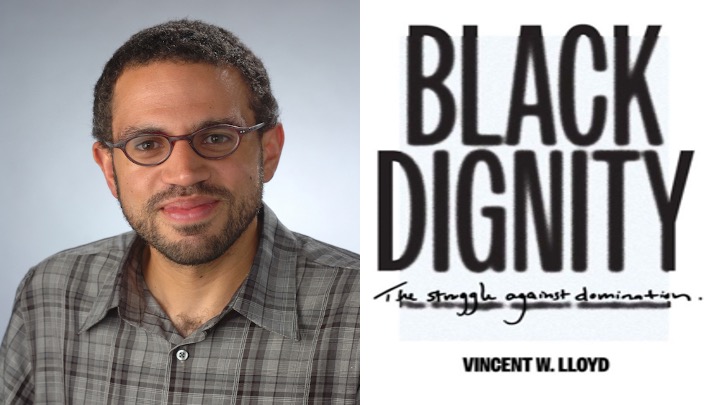

Dr. Vincent W. Lloyd’s latest book, “Black Dignity: The Struggle Against Domination,” explores “the philosophy underlying the Black Lives Matter movement,” the gathering of wills that has defined much of global activism in the past several years. Lloyd’s text is academic—the result of intense interaction with the thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Movement, Black Arts Movement, and various other epochs—but also accessible, dealing with a topic deeply embedded in the everyday American experience.

I recently sat down with the Villanova University professor to discuss his inspiration, the connection between the new book and his prior work, and the call for Catholics and other Christians to grapple seriously with the question of Black worth in the eyes of God and man.

Nate Tinner-Williams: Tell me a bit about what inspired “Black Dignity.” I understand that the Black Lives Matter movement played a part.

Dr. Vincent W. Lloyd: My earlier book, “Black Natural Law,” argued that there is a distinct tradition of natural law reflection in Black Christian communities, one that surfaces in the speeches and writings of Black leaders like Frederick Douglass, Anna Julia Cooper, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. But I also argued that this Black natural law tradition faded during the 1970s, and by the 80s and 90s it was only found in incoherent fragments deployed for partisan political purposes (think Clarence Thomas but also, in a different way, Jesse Jackson).

Then Black Lives Matter happened. It became clear that Black political theology could still animate racial justice movements. Natural law was not part of the movement rhetoric, and movement leaders kept their distance from Christianity. Yet there is a lot of religious language around Black Lives Matter: talk of love, faith, righteous indignation, and spirit, for example. At the very heart of the movement is talk about dignity—it’s in the first line of the Movement for Black Lives platform. To tell a story of Black Lives Matter that appreciates the movement's religious sensibilities, we have to start with what activists mean by dignity. That’s what I try to do in “Black Dignity.”

NTW: Do you consider this text to be a sequel to your previous book, with Dr. Joshua Dubler, “Break Every Yoke: Religion, Justice, and the Abolition of Prisons”?

VWL: In “Break Every Yoke,” Joshua Dubler and I listened to community organizers working to end mass incarceration, and we found a great deal of religious language—and also religious practices, religious emotions, and religious formation. Just like the abolition movement of the 19th century, today’s prison abolition movement is fueled by a theological imagination. Similarly, today’s racial justice movement, at its best, is fueled by a theological imagination. In both the prison case and the racial justice case, when that theological imagination is forgotten, suppressed, or repressed, the movement loses energy and becomes disoriented. Secular politics is the politics of incremental reform and compromise; theologically-informed politics aims at a new world. Faced with moral abominations like human caging and anti-Black racism, we need theology.

There is a significant difference between prison abolition movements and racial justice movements. The latter grow out of the experience of a community that has long suffered from domination and that has cultivated the necessary virtues to survive and flourish in contexts of domination. Indeed, the Atlantic slave trade is the paradigm of domination: humanity is transformed into two identities, master and slave. The legacies of slavery continue to shape the Black experience, in the US and beyond. And the lessons we can learn by attending to the dynamics of domination and Black survival in a world shaped by domination are lessons we need today—lessons Black people need, lessons Christians need, lessons everyone needs.

NTW: Some might be surprised to know, given the work you’re doing, that you teach at a Catholic university. How, if at all, does that interplay factor into your choice to cover topics so intimately connected to the Black experience?

VWL: Villanova, where I teach, is an Augustinian Catholic university. Augustine is the great African saint, and the great African theologian. He grappled with his hybrid identity—one foot in Rome, one foot in Africa—throughout his life and through his profound theological meditations. Augustine invites us to ask, and keep asking: “Who am I?” He sees that question as an invitation to deeper participation in the divine.

I worry that secular discussions of racial justice today, particularly around anti-Black racism, forget that we must all be asking, “Who am I?” Identity labels like racist and anti-racist, oppressor and oppressed, guilty and innocent can be used as conversation-stoppers. Certain activists and intellectuals are canonized (bell hooks, Audre Lorde, James Baldwin), seen as infallible truth-tellers. The Augustinian tradition calls us to ongoing conversation and interrogation that is intellectual and emotional, and that happens in deep, complex community. We must attack domination, humans setting themselves up as gods, wherever we find it—whether that is in slavery, police violence, the prison system, patriarchy, or in the billionaire class. As we attack domination, we must at the same time recognize the boundless complexity of our own identity and of the identities of our friends, our enemies, and our ancestors. These are principles I have learned to embrace through my engagement with the Augustinian Catholic tradition.

NTW: “Black Dignity” includes commentary on a number of Black thinkers not typically associated with philosophy, including Douglass, Lorde, and Langston Hughes—each of whom has unique Catholic connections, by the way. Could you explain how they ended up as focuses in the book?

VWL: I think it’s critical to tap all of the resources we have to challenge domination (which is really a way to talk about challenging idolatry). We need to turn to philosophy, theology, poetry, music, literature, and the visual arts, in addition to the wisdom of our communities and our elders and our own spiritual lives. Yet we need to do this critically: ancestors are not saints. We need to discern what works for us now and what fits with the tradition of Black struggle.

To take one example, Hughes is a brilliant judge of dignity. He notices that dignity is often ascribed in a hollow way, to aristocrats or judges—in short, to dignitaries. Yet those in positions of power have a false copy of dignity. In a poem called “Harlem Dance Hall,” Hughes says that to find genuine dignity we have to look at Black bodies in motion, partially rhythmic and partially improvised, creating spaces that allow for resilience and hope in a space of an anti-Black world.

NTW: What do you think Christians, and especially Catholics, can gain from the study of Black dignity?

VWL: Dignity is a key concept in Catholic social thought, but Catholics do not spend enough time thinking about what dignity really means. European traditions of dignity are still caught up in their aristocratic heritage, privileging comfort and power. Black traditions of dignity force us to discern between hollow copies of dignity, found in the powerful, and genuine dignity, found among the powerless as they organize for liberation.

For this discernment, the Catholic Church has an invaluable resource: the lives, words, communities, and prayers of Black Catholics who have always recognized that dignity entails struggle against domination. In such struggle, we open ourselves to participation in the divine.

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger, a seminarian with the Josephites, and a ThM student with the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA).