In teaching for close to three decades at Xavier University of Louisiana, I have observed my students gradually losing awareness of consecrated life. Many come from high schools founded by religious sisters and brothers. Yet, due to diminished numbers or even a complete absence of religious, most young people today have never met a sister or brother. Every semester I am asked, “What is a brother?” along with questions about a brother’s lifestyle and purpose.

Not long ago, I decided to end my four classes early and ask the students what questions they had about being a brother. Although they initially seemed unaffected by the question, enthusiasm and curiosity clearly emerged, reinforcing the fact that I was the first Catholic religious brother they had ever met. I was the only reference point they had of a brother; therefore they never really thought about our lives.

One male student had attended a school founded by brothers, although absent of them, and he recalled a talk about their charism. Another young man said he could recognize a sister when he saw those who wear habits, and he perceived that their way of life is for God and service. Other than that, he had no idea about brothers.

A basic question about our origins turned the conversation toward the spiritual impetus of our vocation. This gave me an opening to convey that our vocation is a response to God, not a mere human decision or an opting out of other life choices and their responsibilities.

Brotherhood without barriers

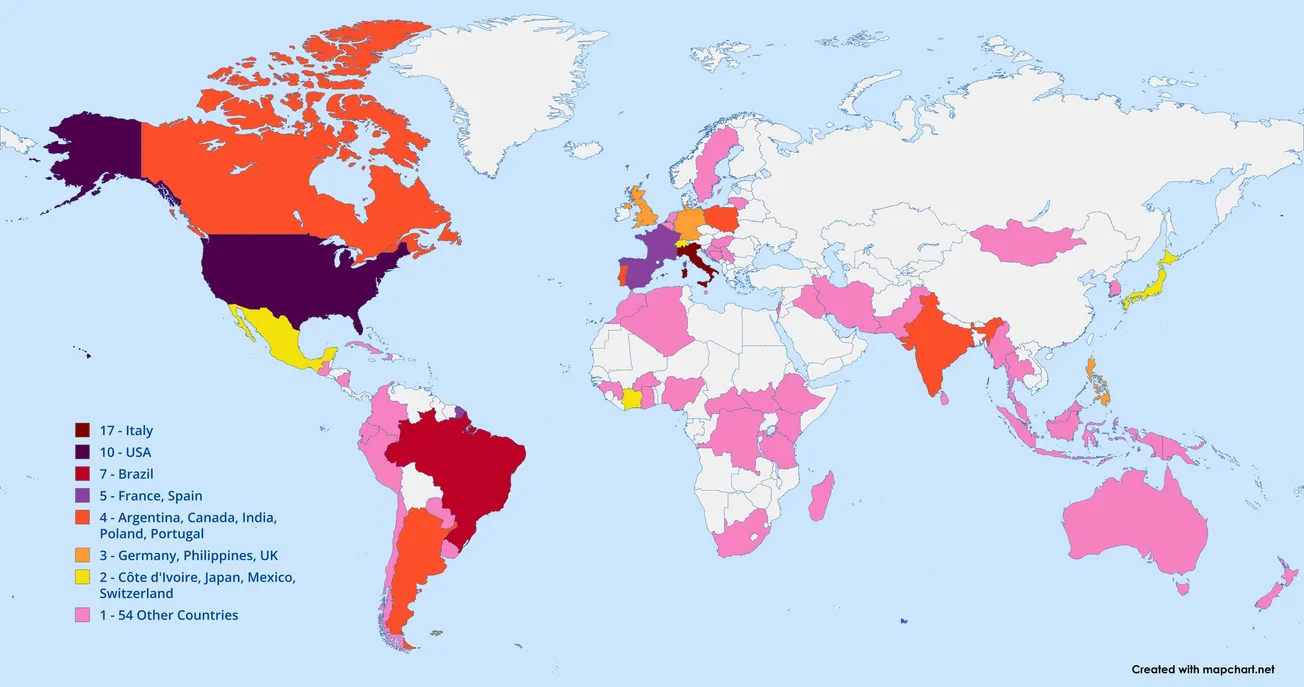

My students are predominantly African American, with a significant Vietnamese presence. The university is 45 percent Catholic, with many of the students coming from Catholic high schools. Despite today’s greater diversity in the priesthood and religious life, for many of these students a Catholic religious is a Caucasian person or, as one student noted, a person from a foreign country, such as India or Africa.

Although their lack of awareness about religious life—and brothers in particular— parallels the wider population’s lack of understanding, I sense that U.S. cultural groups that have not traditionally been in religious life find the vocation to be something that is not meant for them.

My being African American and a religious brother is perhaps the bigger curiosity. They definitely wanted me to personalize the discussion of brothers, to know why I chose this vocation and what sustains me, as I am viewed as a “moderately sane and very happy person.”

The students could connect to my story when I would tell them that my father read me the story of St. Martin de Porres, OP when I was 10. The biggest campus dormitory here is named for Martin de Porres. As such, they’ve heard of him and see his statue in the dormitory foyer.

I tell my students that I related to Martin de Porres initially because he is Black. Later I came to love the things he loved: people and animals. I also consider my learned fluency in Spanish as a mystery attributable to the language he spoke. All these qualities are the stuff of the Spirit, shaping the course of my life and my vocational choice. That’s why I am a Dominican. I strive to be my authentic self as a Dominican brother in the spirit of Martin de Porres.

With St. Martin guiding me over the years of college teaching, I have often wondered what, if any, difference it has made on students’ lives that I am a religious brother. I could humbly say that I have helped support their search for purpose in life. For certain, they come to college for a career, and they hope for a good economic future. But I also hope that their encounter with me is positive and helps them embrace who they are as a gift from God.

My having led a number of post-college men into the Southern Dominican province—four are solemnly professed—says that the mere witness of a single brother can inspire youth to consider their own vocation. Although we brothers are few in number, we can still ignite more brother vocations. In any discussion of vocations, I can never forget that the gospel admonishment to pray to the Lord of the harvest is paramount. All vocational strategies are subordinate to prayer. Vocations are always God’s call, yet we must be bold and invite young men to look at our life.

Prayer and hospitality must be two sides of the same coin. We are presenting a vowed life of poverty, chastity, and obedience, aspects not readily understood or accepted. Therefore our happiness must be evident. People can relate to a happy and friendly brother.

The response of young people to hearing about religious life, and brothers in particular, is very positive. It’s new to them. This generation has no memories of the good sisters and brothers. They have no cherished stories, good as well as not so good, to pass on. As such, my sharing provokes good curiosity. However, it’s too new to provoke guys to follow me to my office to sign up.

At a different level, brothers themselves, and others who believe our vocation is important, can do more to highlight it. When we pray for vocations to the priesthood and religious life, it often seems like we’re talking exclusively of priests, nuns, and religious sisters. It might be better to start saying something like, “sisters, brothers, and priests.” It’s good to see the word “brother” mentioned more in vocational literature, but much more needs to be done.

What I say about who we are

So how does one share the heart and essence of a Catholic religious brother to people who have never seen or heard a brother? When I talk to young people about Dominican brotherhood, I tell them we study a lot—not so much to be professionals, but because gospel living requires lifelong learning. God is not a static, stoic reality but One who is in the stuff of life and our humanity.

We also pray a lot, I tell them, not so much as an expected asceticism, but as a way of staying connected to Jesus who is our life, as a way of really dealing with the challenges of being human. The young fully know about the challenges of life. As such, prayer is sensible for them and an understandable thing to do often.

In conversations about who brothers are, I of course have to explain a little about the vocation in contrast to priesthood, since they inevitably think of a priest in his more identifiable public ministry roles. However, I do not like to say what a brother is in light of what he is not, but rather what he really is. It’s like saying “non-Catholic” rather than identifying the religious faith a person holds.

A priest’s lifestyle is framed by sacramental duties, whereas the brother, like other Christians, seeks to serve God’s people within a range of talents uniquely his. My students see me in the role of their Spanish professor, yet clearly come to know and relate to me as a religious brother. I tell students there are multiple ways God’s love is manifested. The brother manifests one way, a way that is unique and special. A brother models the love of Jesus in the manner he has of reaching out to people. A brother gives witness to Jesus who walked the earth as a brother.

Distinguishing our role as brothers clarifies the beauty and dignity of our vocation. The ministries of most brothers place them among those who have not and might never enter a house of worship. I stress to young people that we are placed in settings like college classrooms among mostly non-churchgoing young people. Our very presence is ministry.

I always start class with 30 seconds of silence acknowledging God’s presence. These 30 seconds are highly appreciated by students. There is for certain a God quest among young people, although for some their faith life is unguided by regular church membership and attendance.

So what do I think the young most need to know about brothers? First and foremost they need to know we exist and we are as significant for this time in history as in days of old. A brother is a man who by his consecrated celibacy has a special availability that yields to service of all people. He is a man who hopefully has a presence that speaks of what I might call the “character of God.”

Brothers are happy, not because of professional accomplishments and acquisitions, but because we are living out our vocation in joy, happy to stay with “yo boy”—as one of my students says in reference to Jesus.

How I invite

I have observed that many young men want to be acknowledged, and they always appreciate time given to them just to chat. How can we invite them to consider being a brother? Simply mention it to them. This simple mention provokes consideration and opens up thoughts about life’s purpose in perhaps a new way.

Asking a young man to consider being a brother can be bold, and responses will range from, “No way!” to, “I’m very honored.” Either way, I pray often about both types of responses. My foundation is the belief that God still calls men to religious life, and that principle can yield results when it is taken to prayer that is followed up by an invitation.

It is important for religious and the whole Catholic community to assist the young in the deep questions of life. For certain, the college student is on a career trajectory. Lifestyle questions have not fully emerged for some. This could be a time of education about consecrated life.

As these conversations happen, I’ve picked up on things about us that are attractive to the young, namely that we live in community and we pray often together. This taps into their own need for communion and belonging. Fraternity is a big attraction for college men. Perhaps belonging to one forever is an initial attention-getter.

They need to know that the concerns of God are what calls us to be brothers and sustains us. We are men of the Word. I do not perceive that the young are turned off by the spiritual underpinnings of our vocation. In fact, they are fully engaged by it precisely because many hunger and hope for something other than what is socially and culturally expected.

In the end, vocations are God’s call. We must challenge the young to at least one time in their life pray and ask God about what their vocation is.

Young people need to know that brothers are ordinary guys who simply love God and try to be love in the world. This is what is most important, and when we brothers live our vocations well, it says a lot more about who a brother is than the best attempts to explain it.

Originally published in the Winter 2018 issue of the National Religious Vocation Conference’s HORIZON Journal. Reprinted with permission from VISION Vocation Guide (vocationnetwork.org).

Brother Herman Johnson, OP is a Dominican brother who lives at St. Anthony of Padua Priory in New Orleans. He teaches Spanish nearby at Xavier University of Louisiana. He holds master’s degrees in Spanish, counseling, and theology, noting: “All professional credentials pale in comparison to my vocation as a Dominican friar.”

Want to support our work? You have options.

a.) give on Donorbox!

b.) create a fundraiser on Facebook