Thursday, August 25, will mark the 115th anniversary of the death of Mother Mary Margaret Healy Murphy, SHSp, a largely muted figure of American (and Black) Catholic history. An immigrant widow-turned-nun, she and the religious order she founded are known for starting San Antonio’s first free private Black school, and the city’s first Black Catholic parish.

What’s more, she might soon become the nation’s latest candidate for sainthood.

Born in 1833 in Kerry, Ireland, Murphy immigrated to the United States in 1845 with her father, first settling in what would soon become West Virginia. There, the young doctor’s daughter first met African Americans—namely the enslaved, some of whom she taught to read and write.

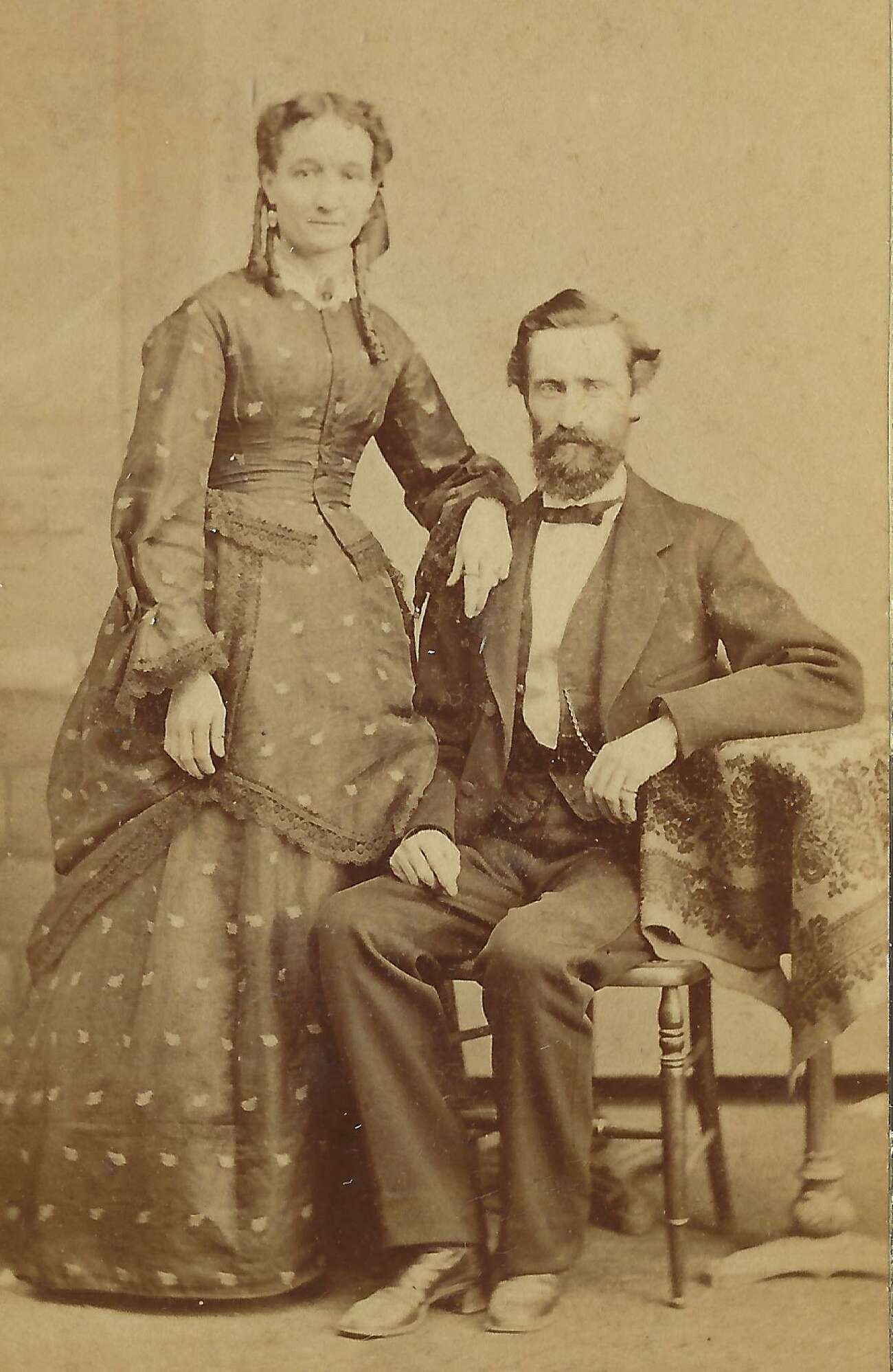

Facing rampant discrimination themselves, the Murphys soon moved westward, eventually landing in Mexico across the border from Texas, then the newest state in America. One of the soldiers from the Mexican-American War, John Murphy, —the future mayor of Corpus Christi—would become Mary Margaret’s husband in 1849.

While it could be said that she was in some ways a Katharine Drexel-type figure on a smaller scale, Murphy departed sharply from the Drexelian ideal in a major way after her marriage. While both were wealthy 19th-century White Catholic women—with Drexel inheriting a fortune from her father, and Murphy from her husband—the latter’s wealth came in large part from a controversial source. Simply put, John and Mary Margaret Murphy owned slaves.

While this fact is not featured in many of the more popular tellings of Murphy’s life—including that of her order, the Sisters of the Holy Spirit and Mary Immaculate—it was known enough in her time that it caused no small controversy after her husband died in 1884 and she dedicated herself to ministry in the Black community.

Left with a large inheritance, Murphy first moved to Temple, Texas to start a Black school there, which was ultimately unsuccessful. Eventually, she decided to try her luck in the Alamo City, and it was there that her efforts became of the most historical significance.

During the Healy-Murphy marriage, the United States had waged its Civil War over the issue of slavery, resulting in the emancipation of roughly 4 million African Americans around the country. Murphy was energized to action upon hearing a sermon from her pastor in 1887, itself inspired by the US bishops’ Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884, where the issue of African Americans was discussed and a call put out for potential mission work.

Murphy soon sold much of her former slave ranch and used the funds to establish the St Peter Claver Mission in 1888. It eventually housed a Josephite church, a school, and a convent for the Holy Ghost Sisters she would found several years later—Texas’ first-ever women’s religious order. (Their current moniker was adopted in 1986.)

The order recently began the process for Murphy’s canonization, and an official biography shared this month for the occasion mentions that she faced harsh criticism for her new ministry, as many of her White peers felt no affinity for African Americans—some of whom were enslaved in the same Irish Texan community just years before.

She had also built the mission in a White neighborhood, sparking the ire of locals and forcing Murphy to resort to legal challenges in order to complete construction, not unlike Mother Drexel’s own dealings in the Deep South. Notably, one reason Murphy started a religious order was to counter the high turnover rate of teachers at her new school, who faced, among other challenges, terrorism from the Ku Klux Klan.

The sisters’ biography of Murphy also mentions, however briefly, that “others within the Church” sought to usurp Murphy’s authority over the mission at one point, “for reasons that are no longer clear.” With an incredulous tone, it notes that in 1894, an attempt was made to boot the Holy Ghost Sisters from the complex entirely, in favor of another order.

Another historical treatment, however, from the late Dr. Philip Lampe, notes that tensions between the sisters and the local Black Catholic community had led to criticisms from both St Peter Claver parishioners as well as from Holy Redeemer, the city’s second Black parish, where they also served. It would appear that the “other order” meant to replace them, unnamed in the sisters’ official biography, was none other than the Sisters of the Holy Family, the order of Black nuns from Louisiana founded by Venerable Henriette DeLille. (Murphy’s sisters in America have attracted few Black women down to the present day.)

Interestingly, Lampe’s monograph of the St Peter Claver Mission goes so far as to link the sisters’ troubles in San Antonio to Murphy’s former slaveholding, as well as her privilege, paternalism, and “demeaning” or “racist” acts perpetrated with perhaps good intentions. Here, too, the similarities with St Katharine are striking.

Whatever the true cause may have been for the Holy Ghost Sisters’ early struggles, their work has continued. That said, the St Peter Claver Mission is no more, save for an alternative school known today as the Healy-Murphy Center, which serves the city’s at-risk teens. The order has also expanded to Zambia and also ministers in Mexico, where Murphy’s southern story began roughly 175 years ago. She died at the San Antonio convent in 1907 at the age of 74.

Her tale in the calendar of the Church is yet to be determined, as her cause for sainthood will go before the US bishops at the hands of Archbishop Gustavo García-Siller, MSpS of San Antonio this November at the USCCB annual fall meeting.

Should it be accepted by the assembly, it would not be a first for a slaveholding American—as that phenomenon began with St Rose Philippine Duchesne in 1895 and was renewed with Mother DeLille in 1997.

Strange though it may be, the story continues.

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger, a seminarian with the Josephites, and a ThM student with the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA).