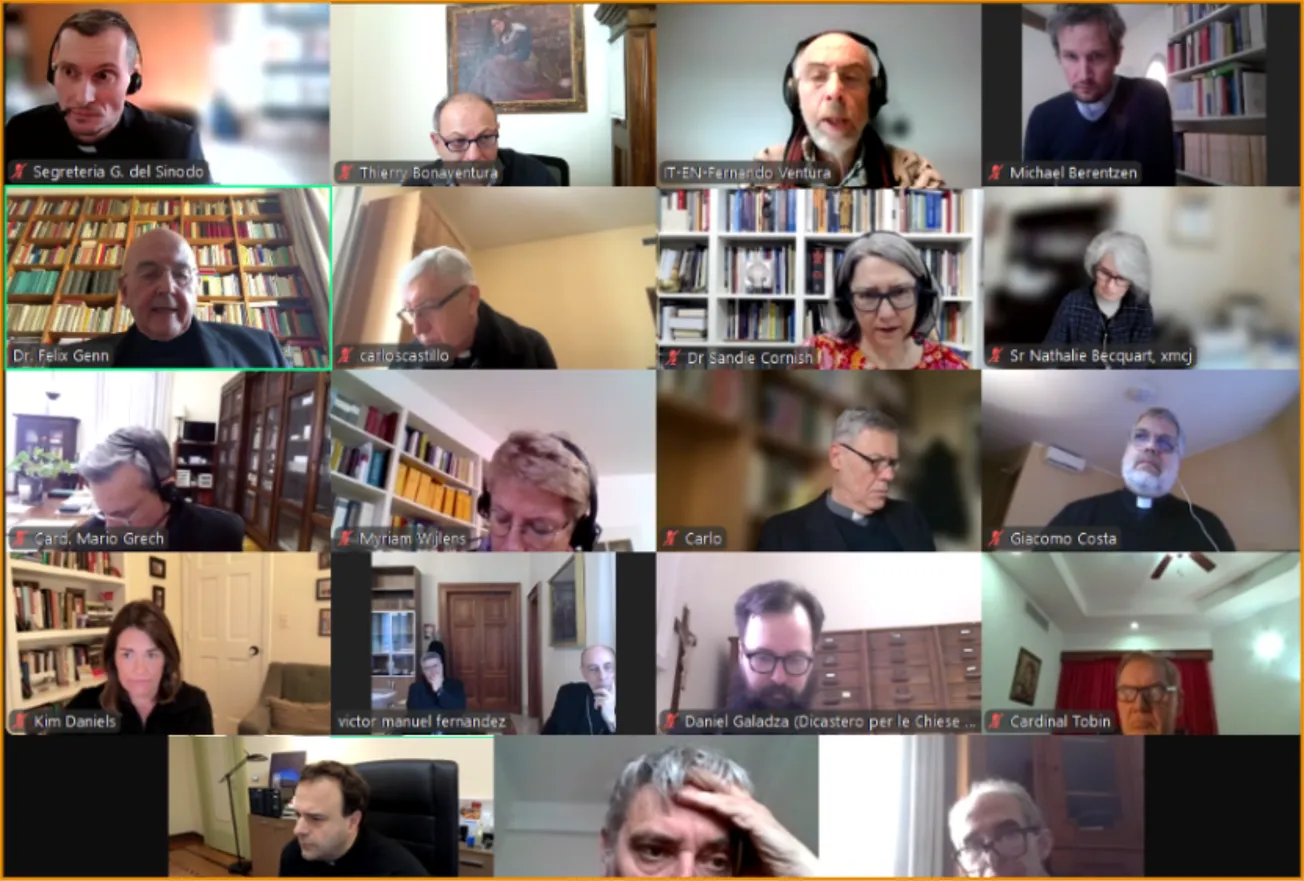

There is “no room” in the Catholic Church for women to receive Holy Orders as deacons, the Vatican’s doctrine czar said during Wednesday’s opening session for the 16th Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops, also known as the Synod on Synodality.

Cardinal Victor Manuel “Tucho” Fernández, prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, made the comments during a presentation of the preliminary work of a study group on “ministerial forms,” under which has fallen the topic of women’s ordination.

“Based on the analysis conducted so far—which also takes into account the work done by the two Commissions established by Pope Francis on the female diaconate (the most useful conclusions of which will be made known in the final version of the document)—the Dicastery judges that there is still no room for a positive decision by the Magisterium regarding the access of women to the diaconate, understood as a degree of the Sacrament of Holy Orders,” reads a transcript of Fernández’ address.

“The Holy Father himself recently confirmed this consideration publicly. In any event, the Dicastery judges that the opportunity to continue the work of in-depth study remains open.”

Here is the translation the Vatican provided. #synod2024 pic.twitter.com/MhmyuZCE9T

— Colleen Dulle (@ColleenDulle) October 2, 2024

It is believed that Fernández’ mention of Pope Francis refers to his May interview with “60 Minutes” correspondent Norah O’Donnell, in which he all but closed the door on the issue. He previously made similar comments in a Spanish-language book released in 2023 prior to the first synod session last October.

Some onlookers, however, have held out hope the landmark gatherings in Rome would somehow provide a way of further discussion on the issue, especially given the number of respondents during worldwide listening sessions over the past three years who expressed concern with women’s role in the Church.

When the hot-button issue was discussed at the first meeting of the synod, a synthesis report approved by the voting body included the issue by a (nevertheless slim) two-thirds margin. Both paragraphs on the topic received the most “no” votes from the delegates—which included women and laypeople for the first time in the history of the Synod of Bishops.

In February of this year, the issue was sent to a study group formed to collaborate with the Vatican for further research apart from the synod itself, which is not expected to rehash the topic during discussions this month. The study group is are expected to conclude their work in June 2025, though Fernández’ address likely gives a clue as to the final product that will emerge in the document they submit to the pope.

Though experts say there is a long history of women deacons in the Christian Church, there is no firm evidence that women received Holy Orders in the sense understood by the Vatican today. The permanent diaconate—whose members do not progress to the priesthood—has only been active in the modern Catholic Church since the Second Vatican Council, which recommended it be restored.

“For centuries, women have served in the tradition of the deacon Phoebe (Rm 16:1). Women of every generation have experienced and expressed their vocation from God to serve the church in ordained ministry,” the Women’s Ordination Conference said in a statement following Pope Francis’ spring interview.

“The church is currently in the midst of a global consultation process, and calls for women’s equitable inclusion in all aspects of church life have been heard on every continent.”

Read our response to Pope Francis on CBS: "No" to Women Deacons? https://t.co/7ln5xR3gpv#OrdainWomen

— Women's Ordination Conference (@OrdainWomen) May 21, 2024

Other Christian groups, such as the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches, remain divided on the issue, with some refusing the practice while others remain open or affirming. The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa was the most recent group to move forward on the issue, ordaining a Zimbabwean woman to the diaconate in early May—after previously ordaining several sub-deaconesses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2017.

In Africa and other parts of the world, the question is largely framed in terms of the need for vocations, which is perhaps most acute in the Western world, where religious disaffiliation and ordinations are inversely related. Accordingly, the Vatican most recently discussed women deacons in depth as part of the Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon region, which took place in Brazil in 2019.

In some of that country’s rural outposts, women often serve in informal leadership positions as a matter of necessity, as do married men. Ultimately, the final report of the Amazon Synod produced no firm answer on whether to admit either demographic to orders not previously available to them.

In the United States, the permanent diaconate is of particular historical significance, given its unusual manner of restoration following Vatican II. Though the council itself had recommended restoration, the U.S. National Conference of Catholic Bishops formally made their request to the Vatican in 1968 largely at the behest of the Josephites—a religious community serving African Americans, whose shortage of ordained Catholic ministers was uniquely acute.

Today, the possibility of Catholic women deacons is viewed in a similar manner, as a way to provide ministers and preachers while also opening to women a segment of the Church long reserved for men alone. Though it seems the pope—and the Vatican—remain open to the idea of non-ordained women deacons, it is unclear how such a framework would address the core concerns expressed by Catholics at the synod and elsewhere.

In the meantime, Cardinal Fernández says his study group has proposed an in-depth analysis of Catholic women throughout history who have “exercised genuine authority and power” outside of the context of Holy Orders.

“This authority or power was not tied to sacramental consecration, as would be in the case, at least today, with diaconal ordination,” he said on Wednesday, suggesting “the recognition of charisms or the establishment of roles of ecclesial service that—while not directly connected to sacramental power—are rooted in the Sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation.”

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger.