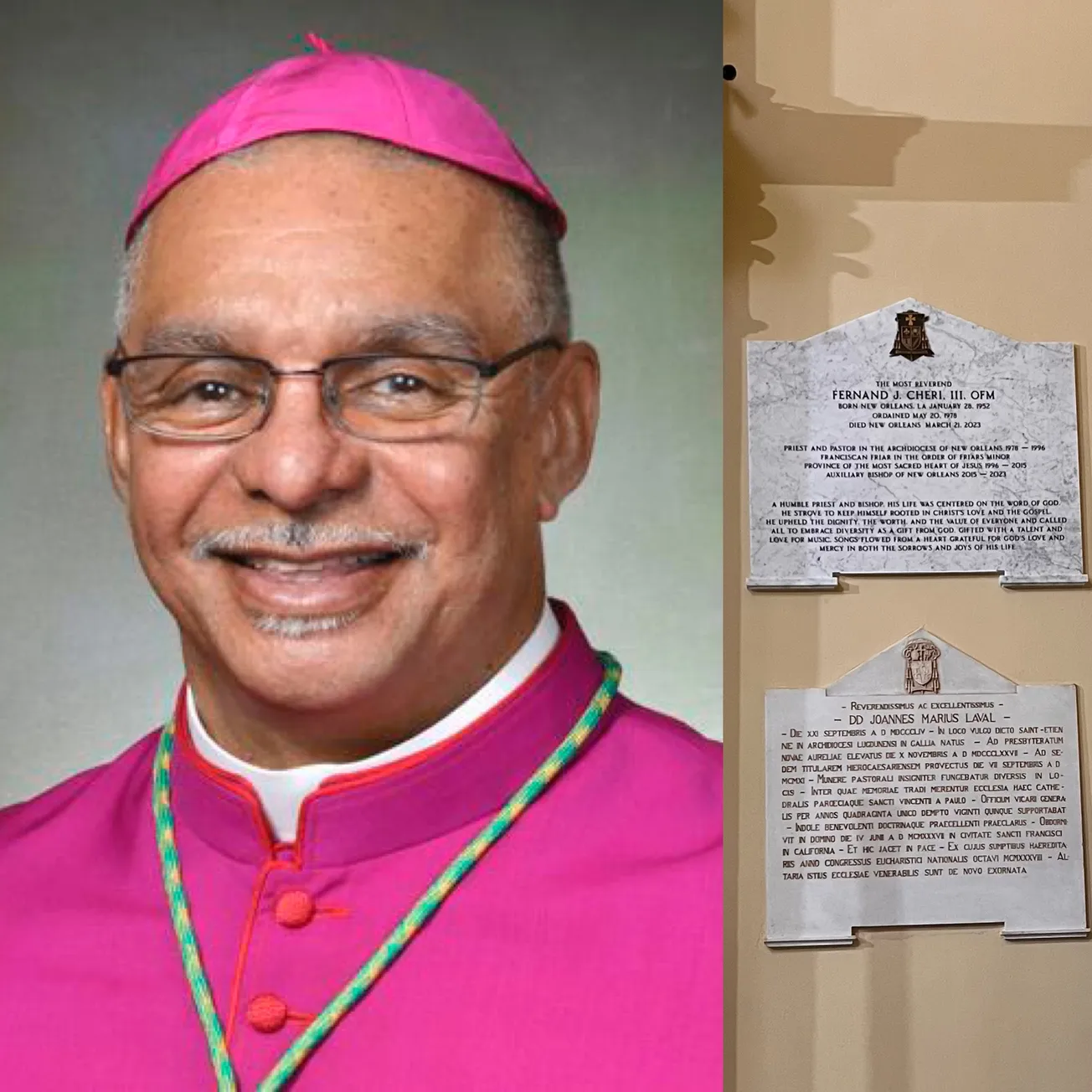

For some years now, there has been a general consensus that one of two men can be considered the first Black Catholic priest in the United States. The first, James Augustine Healy, was ordained in 1854 and passed for White throughout his life, known as Black only to some. The second, Venerable Augustus Tolton, was ordained in 1886 and is well on his way to sainthood.

But what if I told you that long before either man was born—roughly 300 years before, in fact—there was a Black Franciscan priest among the early Spanish explorers of the Southwest?

Let’s start with Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, the upstart explorer who became governor of the autonomous Spanish Kingdom of Nueva Galicia in 1538 in modern-day Mexico. He sent the first Black Catholic explorer of the future United States, Esteban the Moor, on his second trip north in 1539, toward what would become New Mexico. During that journey, Esteban was killed, presumably by Native Americans, and his companion Fr Marcos de Niza, OFM returned to Coronado telling of their majestic city—or Seven Cities—of gold.

Coronado’s interest was piqued, and he set off in February 1540 with a company of troops, indigenous Mexicans, and Africans in search of his mythical “Quivira” in present-day Kansas. Our focus today, however, is the small group of friars who accompanied the group, among whom was the famed American protomartyr Fr Juan de Padilla, OFM.

“Kansas is not in the Southwest!” you might say, of course, and that is correct. Coronado’s expedition would in fact traverse Arizona, New Mexico, as well as the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma before a final trek into central Kansas—where Coronado finally turned back after finding neither gold nor any other riches. He returned to Mexico in 1542, bankrupt and regarded as a war criminal for his actions against the Native Americans.

His journey is not particularly well known to the average American or the average Catholic, and like many narratives of both heritages, the Black members of the expedition seem all but forgotten both in the Spanish colonial records and the modern research which interprets them.

Even so, a letter from Antonio de Mendoza—a major patron of Coronado’s journey—to the Spanish King Charles I reveals that alongside Padilla and the other religious brought along was a “free ladino Black, who was a tertiary and became a Franciscan friar.” (Two other men among the Africans present, Sebastián and Lucas, were allegedly trained by a priest in Mexico, but they may have instead been slaves.)

An earlier translation of the episode, from George Parker Winship in 1896, had termed the unnamed man a “free Spanish-speaking Indian… who passed as a Franciscan friar,” but it is unclear why. The original Spanish text read “un negro ladino y horro que fue de tercero que se metio frayle francisco,” corresponding to the translation from Richard and Shirley Flint in 2012.

Surely it was rather striking, a narrative noting a Black Catholic friar in a region of the world whose Catholic leaders would ban men of African descent from their seminaries up to and including the 20th century. Perhaps for Winship—a Protestant writing in the post-Reconstruction era from a university co-founded by a slavery supporter—the cognitive dissonance was simply too much. A stroke of his pen and the Black priest was no more.

We must, of course, be grateful for the historical correction this decade from the Flints, but they were not the first to the punch. Katheleen Deagan, the groundbreaking archaeologist of Spanish Florida (and specifically Fort Mose, its historic Black Catholic settlement), with Darcie MacMahon authored a scholarly children’s book in 1995 that mentions the 16th century Black Franciscan in passing, noting that he served as an interpreter for Coronado during his expedition.

In 1885, the historian Theodore Hittell has also noted the early “negro priest”, apparently unfettered by the influences that had so thoroughly disarrayed Winship. Hittell, too, mentions the matter in passing, but his note was not lost on one Delilah Beasley. A Black Catholic known for being the first African-American woman published in a major newspaper, she also gained fame for her 1919 book “The Negro Trail-Blazers of California,” compiled from records of early California history.

Beasley gives perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of the anonymous Black Franciscan, including a second translation of the relevant passage by a fellow Black Californian and the following statement:

“It seems passing strange that after hundreds of years, a colored girl and a native daughter of California should be the one to translate this document for its use in the history of the Pioneer and Present Day Negro of California, thereby giving the reading public the knowledge that Governor Coronado on his trip of exploration in an effort to discover in the interest of the Crown of Castile, should have in his expedition several Negroes and even a ‘Negro Priest.’”

Strange indeed. More confounding still is that, despite Beasley’s best efforts, it does not appear that popular Spanish, American, or Catholic history has paid much heed to this tale, its implications, or the larger saga of the Spaniards who first occupied native lands and tilled the proverbial soil of the United States.

Today in Lyons, Kansas, stands the Father Padilla Cross and Historic Marker, memorializing his return to “Quivira” in 1542 with his friars and friends to seek out the treasure of human souls. He was martyred by local Native Americans the same year. Due to geographical dispute, a Father Padilla Memorial Park (with its own historical markers) honors him in Herington, Kansas, some 95 miles away.

In neither monument is any specific mention made of the makeup or fate of his fellow colonists, but we can conclude from the records that at least one Black Franciscan was Padilla’s companion not only in life, but also in death. Several sources agree that the Afro-Spanish priest and interpreter was killed by the Native Americans as well, leaving only one survivor to tell the missionaries’ tale back in Mexico.

On another note, I’ve learned that today is the World Day of Prayer for the Sanctification of Priests, established in 2002 by Pope St John Paul II. The inaugural celebration was inspired by the pope’s preceding three Letters to Priests for Holy Thursday. In 2000, he wrote:

“In this holy room, I naturally find myself imagining you in all the various parts of the world, with your myriad faces, some younger, some more advanced in years, in all the different emotional states which you are experiencing: for many, thank God, joy and enthusiasm, for others perhaps suffering or weariness or discouragement.”

Today, I imagine a young Black Franciscan, halfway across the world from home, on mission in the New World, uncertain of the future but dedicated to his call. He is a Black priestly pioneer, and it’s probably fair to say that he does not need my prayers.

Instead, perhaps in a special way on this day, I think he just might be praying for us.

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger, a seminarian with the Josephites, and a ThM student with the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA).